2002 is still a little bit far away; it was the year when we had the opportunity to read the first comic book published in Spain by a very peculiar Scandinavian storyteller. Born as John Arne Sæterøy, (Molde, Norway; 1965), but better known in the comic-book world as Jason, he was introduced in the Spanish market by the publishing house Astiberri, which brought us Chhht!. This comic-book gave us the chance to visit this author’s particular universe, through a compilation of mute existentialist stories starring anthropomorphic animals that very rarely alter the expressions on their undaunted faces. A static page composition, a very peculiar sense of humor and sensibility, a flawless way of storytelling and a surprising ease to transmit feelings despite -or maybe thanks to- the characters’ hieratical ways became the most appreciable features in this author’s work.

Far from getting too comfortable, Jason has made the most of the last two decades by working on a great variety of genres (sometimes mixing them), which leads to a surrealistic tone in which comedy, absurdity and melancholy go hand to hand. Everything has a place and nothing is superfluous in his comic-books: musqueteers, androids, aliens, zombies, storyteller-turned writers that think about becoming thieves, time-travelling… A seemingly never-ending capacity for fiction, condensed in a bibliography which proves that this unclassifiable author has become one of the most interesting voices in the modern comic-book industry.

Very soon, Jason fans will have the chance to get a hold on a couple of interesting novelties: Athos in America (on sale early January, you can look at the design of the Spanish edition at this link) and the re-printing in a joint volume of Chhht! and Hey, wait… (no date available). But in order to make the waiting more bearable, we offer you the following interview, through which we take a look at his professional career and future plans. Not before thanking the author for his kindness and patience, Astiberri Ediciones for its aid -indispensable for the interview to take place- and Alberto Morán for his support with the translation, let’s get down to business…

Interview with Jason

David Fernández (D.F.).- You have emphasized in many interviews your fascination with The adventures of Tintin, which encouraged you to draw, admiring the author’s ligne claire and, specially, the way he narrates. At which moment did you start to be fully conscious of Hergé‘s talent for storytelling, in addition to the beauty of his drawings? During these first years of contact with the medium, did you try to imitate his style or it just stimulated you to develop your own?

Jason.- In the beginning I just liked the story and the characters. And the simplicity of the drawings might have been one thing that made me try to draw in that style myself. It probably took me some years to realize that simplicity is not easy. It’s often a lot of work behind. So in the beginning I just tried to imitate the style, as best as I could at age 13. There’s nothing wrong in imitating in the beginning. It’s a phase that most cartoonists go through. Finding your own style comes later.

D.F.- Which other cartoonists, you believe, are the most significant when it comes to your vision of the medium and which were the aspects of their work that got your attention?

Jason.- The work of Fabio (Viscogliosi) and Jim Woodring were influental when I started to do wordless comics. This was in my early thirties, when I had already published an album, drawn in a realistic style. I was not totally happy with the result, and it had taken me a long time to do. A year and a half for a 48 page album. So I started trying out other, simpler styles, and this was also the period when I discovered Fabio‘s Vagabond Cat stories and Woodring‘s Frank stories. They appealed to me a lot, both their main characters and also that the stories were told with no text. As a reader you were put into a foreign environment, and with no text that would explain where you were. The stories had a dreamlike quality, something that leaves a lot for the reader’s interpretation. You’re not given all the answers. Hugo Pratt was also a master of the silent sequences.

D.F.- Precisely, one of your strong points is the mastery of a really consistent storytelling, which enables you to play with marked ellipses without affecting the way the story is understood. Is the improvement of that aspect a conscious or unconscious process? Is this aspect of your work a complicated one for you?

Jason.- I guess it’s a both conscious and unconscious process. I wanted to work without words, and in that process discovering that it was a lot easier for me to work that way. I’ve never seen myself as a writer. The things you achieve by using silence is something I realized later, often when asked by journalists. Silence adds mystery, I think. And it’s more inviting for the reader, I feel, to participate in the story.

D.F.- When it comes to developing your own style, the influence of ligne claire was reflected in your synthesis capacity and, as we previously mentioned, in the storytelling aspect of the book. But it wasn’t quite reflected in the attention to backgrounds, an aspect in which Tintin’s creator was a total master. Do you believe that you can blame that fact on –in your own words– a «weakness as an artist«, or is it a conscious and premeditated graphical option, part of the kind of stories you wanted to create?

Jason.- Yes, I think partly it comes from your weaknesses as an artist. I prefer to draw the characters. I’m not that fond of drawing backgrounds, so I keep them as simple as possible. Just to establish where the characters are, that’s enough. And I prefer the early Tintin albums that had that simplicity. A couple of lines to show the buildings in the background, a couple of bricks in a wall. The perfect backgrounds that came later appeal less to me. It’s not something I try to copy.

D.F.- Your first work can be set at 1981, during high school, when you debuted at the humor magazine KonK. Is it possible to appreciate in these first projects any of your style’s current characteristics, or did you use a different one? Which kind of stories did you create back then?

Jason.- No, the early stories and cartoons I did weren’t good. And you can see what comics I had read that week. Sometimes it’s Hergé, sometimes Morris and sometimes Don Martin. And mostly I screw it up, of course. But yes, a lot of the stories has that type of absurdity you find in Don Martin.

(click on images to get a larger size)

D.F.- Part of your education as an artist took place at Norway’s National Academy of the Arts, where you studied graphic design and illustration. Did comic books get a positive academic recognition at this institution, or you found indifference and disregard towards this medium? Which knowledge acquired during this period was the most useful for you?

Jason.- It wasn’t really an Academy of the Arts. It was not a school for artists, like painters and so on. I’m not sure what the best translation of the name would be. National School for Art and Design, maybe. So it was a school for illustrators and graphic designers. To be a cartoonist in Norway at the time, to have it as a living, was difficult. The school wanted us to find jobs when we were finished, not to stand in an unemployment line. But at the same time, they were not hostile to comics. The fourth year there was a three week course in comics, which I took. I didn’t learn anything new, really, since I had already done comics. But it was not my intention to be a cartoonist at the time. I wanted to become an illustrator, to have an income from that, and to continue to do comics as a hobby.

D.F.- You have stated in previous interviews that when you stated working in comic books, the industry’s situation in Norway was quite poor. In which moment did you start to be conscious about the fact that your hobby could become your job?

Jason.- Oh, it took a long time. Ten years maybe. Where I tried to make a living as an illustrator, without too much luck. There was a period of two years where I was on the dole. Those two years I did nothing but comics, and my comics improved a lot during those two years. But I didn’t make much money from those comics. You don’t do comics for the money. You do it for love of the medium, for the need to tell stories in images. It’s not necessarily a bad thing. You feel a connection to other struggling cartoonists. It’s something you have in common. There some humility in it. So there are very few cartoonist assholes. I haven’t met any.

(click on images to ger a larger size)

D.F.- After winning the Norwegian Comics Association Award for Pervo and with Pocket Full of Rain released, you started to publish your own comic book with certain periodicity: Mjau-mjau. How did you get this chance? Was it a fully self-edited project?

Jason.- I met other cartoonists in Oslo. There was a small scene. And from that came Jippi Publishing, an underground or alternative publishing house. There were grants that you could apply for. You could get a comic book published, usually around 1000 – 1500 copies. And yes, it was self-edited. You had complete freedom. No one told you what to do.

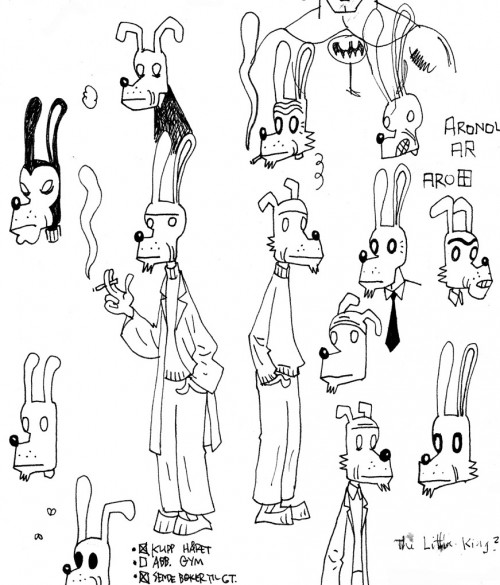

D.F.- If I’m not wrong, Mjau-mjau was the first project in which you created stories starring anthropomorphic animals; an idea that nowadays has become one of your trademark features, perfect for that stories with a fable flavor that didn’t flow through realistic ways. In which moment did you consider that there was no turning back and that your stories and tastes fitted better in an anthropomorphic universe? Is there any chance that you work in a project in which you drop this feature?

Jason.- It happened almost immediately. It felt right from the beginning. It was the kind of stories I wanted to tell, and the animal characters felt right for those stories. I’ve never really looked back since then. I’ve never thought about going back to drawing in a realistic style. I don’t see any limits in the animal characters , that there are stories you can’t tell. Rather the opposite. Look at Maus. Would it have worked as well in a realistic style. Maybe. But it wouldn’t have been the same.

D.F.- Another very recognizable aspect of your work is the hieratic nature of the characters. Their rigid expressions are, paradoxically, very evocative. It’s like those almost inalterable gestures turned into blank canvases over which the reader can project his own interpretation of each fiction, strengthening in many occasions the absurdity, irony, sense of humor, paradox and melancholy of your stories. Do you believe that, in a way, you force the reader to a great exercise of participation and immersion? May this be one of the aspects of the medium that attracts you the most, compared to other arts?

Jason.- Yes! All of that. That’s why I do the expressionless faces. I’m not sure I knew that at the time. Again, it’s by answering questions from journalists that i’ve discovered what you acchieve by doing that. The reader has to put his own thoughts and feelings into the characters. I don’t think it’s something uniqe for comics. It’s something I’ve mostly picked up from films. Buster Keaton, (Robert) Bresson, Aki Kaurismäki.

D.F.- In spite of such a trademark sensibility, truth is that you have seen your work recognized with such prestigious awards as the Ignatz, Harvey or Eisner Awards, and your books are published in many countries. Did you expect this kind of acceptance?

Jason.- I’ve been nominated for an Ignatz, but I didn’t win. No, no, I didn’t expect any of that. It still doesn’t feel real. It’s nice when it happens, I appreciate it. Hopefully you reach some new readers. But at the same time, it doesn’t change anything. It doesn’t make it any easier to do the next book. You always start with the blank paper.

(click on images to get a larger size)

D.F.- On the other hand, during the last years you have lived in Denmark, Belgium, the United States and France. Do you feel that these countries and their cartooning tradition and general culture with regard to comic books have had an influence in your work?

Jason.- No, I think my style was already set before moving abroad. But living in France where comics are viewed as an artform is very different than living in Norway. But funnily enough, French cartoonists still complain about comics not being taken seriously. So even France is no Nirvana for comics.

D.F.- In other interviews you have mentioned the fact that due to your visual way of thought (“I think more in images than in words”), you find it difficult to write dialogues. However, just like the gestures of your characters, the low dialogue frequency emphasizes its presence. With time, you have developed astonishing subtlety and precision. Are you more satisfied now with your work as a dialogist?

Jason.- I guess. It was a challenge writing dialogues. That is why I stopped doing completely wordless comics. But I still believe in silence, that some sequences work better without any text. But drawing can be a lot of work. It’s not the fun part of comics. That happens when you write a piece of dialogue, and then wonder where that came from. When the characters write themselves. That doesn’t happen all the time, but sometimes.

D.F.- It’s quite evident that your love for films has also played an indispensable role in your authorship: you have incorporated to your work certain appreciable characteristics from the movies of unique filmmakers such as Jim Jarmush, Aki Kaurismaki, Hal Hartley or -maybe the most evident cases- Buster Keaton and Alfred Hitchcock. Could you kindly specify the way each one of them has influenced your style and conception of the fiction genre, translated to the comic book language?

Jason.- I think I learned minimalism from Jarmusch and Kaurismäki. To keep it simple. That you don’t need to change the angle for each panel. That how the character moves means something. If he looks down, it means something. From Hal Hartley I think I learned that dialogue doesn’t necessarily have to be realistic. Sometimes it can be theatrical. Sometimes it can be absurd. These are things I should have learned from the theatre, I guess, but I never go to the theatre, so I had to learn it from Hartley.

D.F.- This love towards films is also appreciated in the constant use of genres that we find at your work, mixing adventures, science fiction, zombies, noire genre, comedy, western… Which role do you think the disconcertment this mix causes -brought to its peak in I killed Adolf Hitler, The Last Musketeer or Low Moon– and the feeling of familiarity among readers with certain trademark codes of these genres play in order to get their complicity, accepting the suspension of disbelief?

Jason.- I don’t know. Those are things I never think about. If I do a do a story from some film genre, it’s because I like those films. Like the old science fiction serials, like Flash Gordon, that was the inspiration for The Last Musketeer. But it’s never a parody. I don’t mock anybody. And it’s not to be clever. That’s seldom interesting. Mostly it’s just a way for the story to start. Like Werewolves of Montpellier. It’s not really about werewolves.

D.F.- Despite this predilection towards genres, some of your first works such as Hey, Wait… had a more dramatic or intimate undertone that has not disappeared in later works: on the contrary, it has integrated in a context of «genre collage». How do you value this process?

Jason.- I guess the later stories are more playfull than what Hey, wait… was. They are more fun. I think that was a conscious decision. I wanted less darkness. But it’s still there, I think, a certain melancholy. It’s something that just happens. It’s who I am, I guess.

(click on the images to get a larger size)

D.F.- Another very interesting aspect of your work is the composition; what I mean with it is that you usually use a static page planning for each work: 2×2 panels in Low Moon, 2×4 in I killed Adolf Hitler and Werewolves of Montpellier, or 2×3 in the Almost Silent compilation. Despite this, the result is not reiterative for the reader and the narration is not affected. Why do you choose this option and what criteria do you follow to choose a certain composition or another?

Jason.- I like the grid. To not change the panels. But why should you? It’s the story that is important. Fancy pagedesign can often just get in the way. I’m not sure if there is any big thought process behind it. It’s sort of organic. If I’ve done 3X3 in one album I might try 2X4 in another.

D.F.- Since 2002, the year in which you started to focus on your own graphic novels, you have been progressively adopting certain changes, occasionally adapting yourself to the 48 page format and publishing your work in color. I’m especially interested in this aspect, from a creative standpoint: how has the collaborative process with Hubert Boulard evolved and how did you plan this change, considering the attention you pay to narrative and the influence of the chromatic element over it? Do you address many indications and corrections?

Jason.- I wanted to make comics as a living, and that’s easier when you work in colour. At least the Francobelgian 48 page albums are always in colour. It was my publisher at Carabas that found Hubert, and i’ve been very happy with his work. There was some indications in the beginning, that I wanted flat colours without toning and so on, but since then I’ve learned to stay out of his way. I check the pages before they’re printed, but that’s mostly just to see if there are any direct mistakes.

D.F.- You’re used to working with your own material; however, you have broken this tendency in certain occasions: firstly, with the comic book adaptation of the novel The Iron Wagon, by Stein Riverton (pseudonym of Sven Elvestad) and later, with Isle of 100,000 Graves, in collaboration with Fabien Vehlmann. In one of these cases you transferred novelistic material to the comic book language of the story and in the other, you collaborated with other writer. How did you live these experiences, in which you didn’t have full creative control? Would you repeat this way of work, being part of a creative team?

Jason.- Sure, I’d like to do that again. I had fun drawing pirates in Isle of 100 000 Graves. But at the same time I realized that just drawing is a bit less interesting. It’s creating the characters and dialogues that is interesting. We’ll see. As long as I have ideas for stories myself, I’d rather write the script myself, but I expect that I’ll run out of ideas someday, and then I wouldn’t mind working with another writer.

(click on the images to get a larger size)

D.F.- Soon, Astiberri will publish the Spanish edition of your new work: Athos in America, a book comprised by short stories, in which you get back some characters that appeared on The Last Musketeer and Low Moon. What can you tell us about this project? In which new books are you working right now?

Jason.- It’s a collection of short stories, in the same small format as Low Moon. Athos from The Last Musketeer appears in one story. It takes place in New York in 1920. Athos tells about his adventures in America. There’s another story, The Smiling Horse, where we meet again the two main characters from & in Low Moon. I tried out different drawing styles in each story. Drawing with a pen with an ink cartridge, so that you don’t have to dip it in ink, I went back to using a brush, and I did one story where I also used a colorpencil to lay in shades. There’s one story without any dialogues, all the text is in word balloons. So it’s a slightly experimental collection.

D.F.- Can you tell us about your usual work procedure, when working alone, regarding the writing of the script, the sketching, drawing, inking, type of paper and other materials?

Jason.- I don’t write a full script. The stories are mostly done by improvisation. Sometimes I write the text first. Other times I make the drawings first and then put in the text later. Sometimes I make small sketches, thumbnails, other times I just draw directly on the original. I usually work on nine or ten pages at the same time, going back and forth, penciling a bit here, then inking it. I don’t use any particular paper. The important thing is that the line doesn’t bleed. The pen nib I use is a Mitchell Pedigree Round Hand, size six, which really is a lettering or caligraphy pen, but I also use it to draw with. You get a nice variation in line thickness.

(click on the images to get a larger size)

D.F.- Considering the release date of KonK (1981), this year has been the 30th anniversary of your career. And, almost coinciding with this date, you have started a couple of blogs in which you show us old works and previews of the comic books you are currently working on, but also literary and film reviews. On the basis of this reflection process -more or less conscious- regarding your career, old and current projects, and favorite themes, which conclusions do you get? Which are your greatest achievements, your peaks as an author and the subjects that you still have pending?

Jason.- I don’t know. I guess the greatest achievement is that I make a living doing comics, something I never expected. I bought an apartment last year, with money made from doing comics. As for future challenges, I want to do longer stories, 150-200 pages. So far I’ve mostly done shorter stories and the French 48 page albums. But really, just to continue making comics for a living. I can’t imagine any other job I’d like.

- We begin this section doing reference to Jason’s official weblog: Cats withouts dogs, where the norwegian author not only publishes different different drawings, but also lists and reviews focused on his cinematographic, musical or literary preferences.

- He also finds time to publish contents on another blog: The old cat and the dog, where he rescues old works.

- Searching around the Internet, it’s possible to find different biographic and bibliographic profiles, whith information about his formation as an artist, as well as the norwegian artist’s proffesional career: on Astiberri and Fantagraphics‘ websites, but also on english Wikipedia and the french one, on Lambiek, Comic Book Database and BD Gest’, besides this fan site on Facebook.

- On our review index it’s also possible to find some posts focused on Jason’s works, like: The iron wagon (1 and 2) and Werewolves of Montpellier.

- Last but not least, a bunch of interviews given by the norwegian cartoonist: to AICN Comics, Comic Book Resources, where he repeated at least twice (1 and 2), Comic Book Bin, The Comics Reporter, The Casual Optimist, Newsarama, The Daily Cross Hatch (parts 1 and 2, translated into spanish on the blog 999), Panels and Pixels, Charcos de tinta, Ciudadano Pop and Klare lijn international (translated into spanish by Entrecómics).

Hi there, its nice paragraph regarding media print, we all be aware of

media is a fantastic source of data.